User’s Guide for Program RLAPL

Scalar Potential in Resistors of Varying Geometry and Resistivity

C.W. Trueman

September 20, 2000.

Updated September 25, 2001.

Consider the problem of

finding the resistance of a resistor of uniform thickness t. The resistor has two metallic terminals, one

at potential ![]() volts and the other

grounded. The resistor can have any

arbitrary shape in the xy plane provided that its thickness is uniform. The resistivity of the material

volts and the other

grounded. The resistor can have any

arbitrary shape in the xy plane provided that its thickness is uniform. The resistivity of the material ![]() can vary throughout

the resistor. The problem is to find

the scalar potential

can vary throughout

the resistor. The problem is to find

the scalar potential ![]() in the resistor, and

hence the current flow at each point in the resistor,

in the resistor, and

hence the current flow at each point in the resistor, ![]() where

where ![]() . The current flow in

the resistor can then be found by integrating the current density over a

cross-sectional surface in the resistor.

. The current flow in

the resistor can then be found by integrating the current density over a

cross-sectional surface in the resistor.

This User’s Guide presents a

finite-difference method for finding the scalar potential and hence the current

flow in the resistor. The method is

implemented in a program called RLAPL.

First the update equation for the finite-difference method will be

derived, and then the input commands for the RLAPL program are given. Some simple examples are then solved.

Students wishing to use

program RLAPL should read the user’s guide for program LAPL, which solves

Laplace’s Equation in regions of space filled with dielectric, such as coaxial

cable. The LAPL user’s guide provides background needed to understand the

following. To get a copy of the “exe”

file for the program, click the mouse here:

Get rlapl.exe.

The Partial Differential Equation for the Scalar Potential

This sections obtains a

partial differential equation(PDE) that the scalar potential ![]() satisfies in the

resistor. Since there is no stored

charge in the resistor,

satisfies in the

resistor. Since there is no stored

charge in the resistor, ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() and

and ![]() we can carry out some

substitutions to derive the PDE, as follows.

we can carry out some

substitutions to derive the PDE, as follows.

Starting with

![]()

substitute ![]() where

where ![]() , and

, and ![]() to obtain

to obtain

![]()

A resistor of uniform thickness t is a two-dimensional problem

in which the scalar potential ![]() is a function of

is a function of ![]() and

and ![]() only. Expanding the divergence and gradient in

rectangular coordinates obtains

only. Expanding the divergence and gradient in

rectangular coordinates obtains

![]()

hence

![]()

Note that if the conductivity ![]() is uniform, that is,

not a function of

is uniform, that is,

not a function of ![]() or

or ![]() , then this equation reduces to Laplace’s Equation. Hence Laplace’s Equation is the special case

of uniform conductivity.

, then this equation reduces to Laplace’s Equation. Hence Laplace’s Equation is the special case

of uniform conductivity.

The Update Equation for the Finite Difference Method

Consider a finite difference

solution of the PDE in a cell space of cell size ![]() having cells numbered

having cells numbered

![]() in the x

direction and

in the x

direction and ![]() in the y

direction. The centers of the cells

will be denoted by points

in the y

direction. The centers of the cells

will be denoted by points ![]() and the scalar

potential at the center of cell i,j is

and the scalar

potential at the center of cell i,j is ![]() .

.

To derive an update equation

for a finite-difference method, we need to approximate the partial derivatives

with the central difference formula. Let point “b” be half way between ![]() and

and ![]() and point “a” be half

way between

and point “a” be half

way between ![]() and . Then

and . Then

The partial derivatives at “a” and “b” are approximated as

![]()

and

![]()

To approximate the conductivity ![]() at “b” we can

consider current flowing from

at “b” we can

consider current flowing from ![]() to

to ![]() . For half the

distance the resistivity is

. For half the

distance the resistivity is ![]() and for half the

distance the resistivity

and for half the

distance the resistivity ![]() , so we have two resistors in series, each of length

, so we have two resistors in series, each of length ![]() . The resistance is

. The resistance is

![]()

where t is the thickness of the resistor. This can be written as

hence the equivalent resistivity for current flow from ![]() to

to ![]() is the average,

is the average,

![]()

where the “r” superscript stands for “right” and denotes the average

resistivity at the cell wall to the right of node i,j, which is point ![]() . Define the “right”

conductivity as

. Define the “right”

conductivity as

![]()

From above,

hence can now write the complete approximation to the first term in the

PDE as

![]()

Similarly if we define the

“top” conductivity as

![]()

then we can approximate the

2nd term in the PDE in a similar way. Inserting the approximations into the PDE and rearranging

obtains the update equation,

![]()

where

![]()

The “right”, “top” and

“tilde” conductivities can be computed as part of the initialization of the

program and stored in an array, and recalled when the update equation is

applied to cell ![]() .

.

Program RLAPL

Program RLAPL implements the method described above. To learn to use RLAPL, read the “LAPL User’s Guide” for the Laplace’s Equation solver called “LAPL”. RLAPL and LAPL are set up the same way and many of the LAPL commands will do the same thing in RLAPL. The following briefly describes the commands that are new in RLAPL and then gives some examples of calculations that can be done with RLAPL.

Table 1 lists the input commands

for program RLAPL and Table 2 is an input file which models a simple

resistor. The user should include

comments in the input file describing the purpose of each line in the file,

using the CM command. The cell size is

set with SIZE, in meters. The size of

the space is set with SPACE. By

definition all the edge cells in the space are metallic cells and are set to

zero potential. Some of these cells can

be reset to 100 volts or some other potential, but these cells cannot be

resistive cells or insulators. The

thickness of the resistor is set with THICKNESS, in meters. All the cells in the cell space, except the

metallic edge cells, start out as insulators, with a very high resistivity. A line of cells can be set to a desired

resistivity, say 10 ohm-m, with the RESIS_LINE command. All the cells inside a rectangular box can

be set a desired resistivity with the RESIS_BOX command. We can define metallic terminals for our resistor,

set to fixed potentials, with LINE, CIRCLE, CSHELL and ELLIPSE, as in program

LAPL. To find the resistance we set

one terminal of the resistor to a fixed potential such as 100 volts and the

other terminal to zero volts. Then we need to know the current flow I in the

resistor, so we can evaluate ![]() ohms. Use the command CURRENT to draw a line

across the resistor, either vertically or horizontally. The program will calculate and report the

current flowing across this line. Thus

in Table 2 the user asks for the current across a line at cell 10 axially, cutting

across the full width of the resistor from cell 1 to cell 54.

ohms. Use the command CURRENT to draw a line

across the resistor, either vertically or horizontally. The program will calculate and report the

current flowing across this line. Thus

in Table 2 the user asks for the current across a line at cell 10 axially, cutting

across the full width of the resistor from cell 1 to cell 54.

The commands for controlling iteration in RLAPL are the same as those in program LAPL. Usually a large number of iterations such as 20,000 is required, and it is convenient to have the program update the graphics display every 1000 iterations so that you can monitor the progress of the computation.

Program RLAPL creates two “table” files for graphing with CPLOT. The scalar potential is saved in VOLTS.TBL and the magnitude of the electric field vector is saved in EFIELD.TBL. Note that the value of the current is written into the header in VOLTS.TBL, in case you forget to note it when it appears on the computer screen.

Table 1

Input Commands for Program RLAPL

|

Purpose |

Command |

|

Include a descriptive comment in the input file |

CM followed by your text |

|

Specify the cell size (meters) |

SIZE 0.01 |

|

Specify the size of the finite-difference cell space |

SPACE 10 12 |

|

Define the thickness of the resistor |

THICKNESS 0.001 |

|

Set the resistivity of a line of cells to 10 ohm-meters |

RESIS_LINE 2 3 45 52 10. |

|

Set the resistivity of a box of cells to 10 ohm-meters |

RESIS_BOX 2 3 101 52 10. |

|

Define a line of cells as an insulator |

INSUL 2 2 101 2 |

|

Define a line of cells at a fixed potential |

LINE 10 10 20 10 0. LINE 10 10 10 20 100. |

|

Define a solid cylinder of cells at a fixed potential |

CIRCLE 50 50 10 100. |

|

Define a hollow cylindrical shell of cells at a fixed potential |

CSHELL 50 50 40 0. |

|

Define a hollow elliptical shell of cells at a fixed potential |

ELLIPSE 50 50 60 30 0. |

|

Find the current flowing across a line |

CURRENT 10 1 10 54 |

|

Specify the total number of iterations to be done |

NSTOP 10 |

|

Pause the program after updating each cell |

SINGLESTEP |

|

Redraw the potentials after 10 iterations of updating the cell space |

NUPDATE 10 |

|

Pause the program after redrawing the potentials |

PAUSE |

|

Mark the end of the input file |

END |

Simple Resistor

Find the resistance of a resistor of thickness 1 mm, resistivity 10 ohm-m, measuring 1 cm long and 0.5 cm wide.

Answer: ![]() ohms

ohms

To model this with RLAPL,

choose a cell size of 1 cm / 100 cells = 0.01 cm = 0.0001 m. The resistor is 100 cells long by 50 cells

wide. Table 1 gives the input file. The input for program RLAPL is quite

similar to that for program LAPL, and users should read the “LAPL User’s

Guide”. In Table 2, SIZE sets the cell size to 0.0001 m. The thickness of the resistive material is

set to 1 mm with THICKNESS. The size

of the cell space is set to 102 by 54 cells.

Lengthwise, 102 cells is made up of 1 cell for the 100-volt metallic

contact at left, 100 cells for the 1 cm body of the resistor, and 1 cell for

the grounded metallic contact at the right.

Crosswise, 54 cells is made up of 1 cell for the metal boundary of the

cell space, 1 cell for an insulator to

separate the body of the resistor from the metal boundary, 50 cells for the

half centimeter width of the resistor, plus one cell for an insulator and 1

cell for the metal boundary. The resistivity

of the body of the resistor is set up with the “RESIS_BOX” command, which sets

all the cells inside the rectangle from cell 2,3 to cell 101,52 to 10

ohm-meters resistivity. Note that we do

not set the cells from 2,2 to 101,2 or from 2,53 to 101,53 to be

resistive. These cells are the

insulator separating the resistor from the metal boundary of the cell

space. Next the 100 volt terminal of

the resistor is set up with a LINE of cells at 100 volts from cell 1,3 to cell

1,52. The 0 volt terminal is set up

with a LINE of 0-volt cells from 102,3 to 102,52. Because the edge cells are already at 0 volts by default this

could be omitted. The insulators

separating the body of the resistor from the metal wall at the bottom and at

the top are explicitly defined with “INSUL” commands. These set up a line of insulating cells from 2,2 to 101,2 and

from 2,52 to 101,53. Since the cells

are insulating by default, these commands could also be omitted. Including these commands makes the user’s

intentions clear and someone else reading the file will understand that these

cells are specifically intended to be insulating cells. The input file finishes by specifying 20,000

iterations be done and that the graphics screen be updated every 1000

iterations.

Table 2

Input file for

program RLAPL to model a simple resistor.

|

CM

Simple resistor for solution with RLAPL CM

CM

Resistor 1 cm long by 1/2 cm wide. CM

Thickness 0.1 cm CM

Resistivity 10 ohm-meter CM CM

CELLSIZE (in meters) is 100 cells= 1 cm or .01/100 = 0.0001 SIZE 0.0001 CM

The thickness of the resistive material: THICKNESS 0.001 CM CM

The resistor body will be 100 by 50 cells. CM

In addition, there is a 1 cell boundary all around the edges, CM

which is by definition a metal. We

need an insulator 1 cell CM

wide along the sides, to separate the resistor body from the CM

metal wall. This makes the width of

the cell space 4 more cells CM

than 50 cells=1/2 cm. SPACE

102 54 CM CM

Define the resistivity of cells in the body of the resistor CM

This fills a box 100 cells long and 50 cells wide, from cell 2,3 CM

to cell 101,52, with material of resistivity 10 ohm-meters. RESIS_BOX

2 3 101 52 10. CM CM

Define the metal contacts on the ends of the resistor. CM

The left edge where the current enters is at 100 volts: LINE

1 3 1 52 100. CM

The right edge where the current leaves is at 0 volts: LINE

102 3 102 52 0. CM

Note that all other boundary cells are grounded by definition, CM

so this last "LINE" command is not really needed. CM CM

Define the insulating boundaries along the sides. These cannot include CM

any edge cells: INSUL

2 2 101 2 INSUL

2 53 101 53 CM

Note that these “INSUL” commands are not really needed, either, CM

because all the cells in the cell space start out as "insulator"

cells CM

by default. CM CM

Find the current flowing across a vertical line centered at CM

cell I=10 cutting across the full width of the cell space from CURRENT 10 1

10 54 CM CM

Number of iteration between screen updates: NUPDATE 1000 CM

Total number of iterations: NSTOP 20000 CM END |

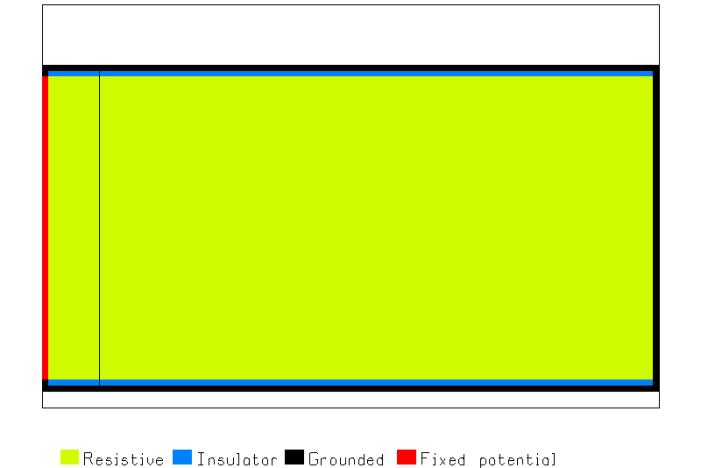

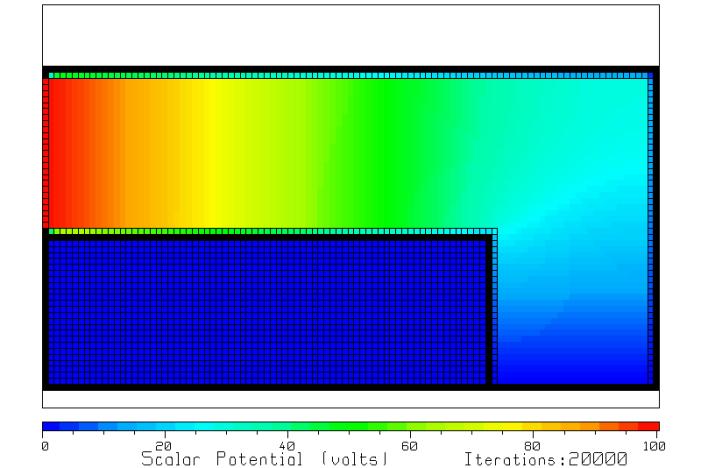

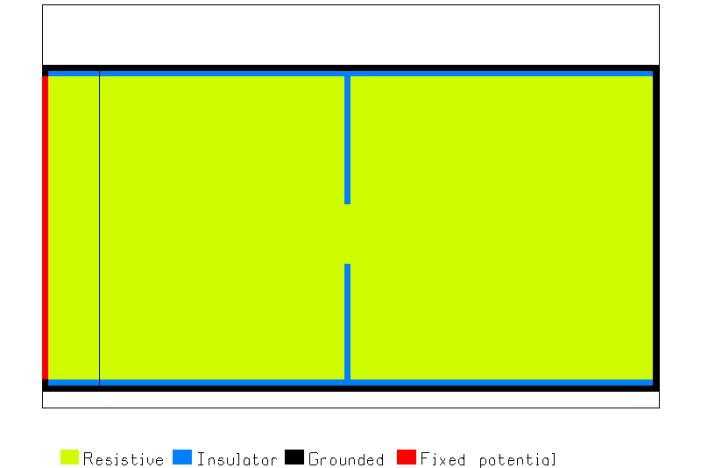

Figure 1 A simple resistor

consisting of insulating walls at bottom and top, and a uniform resistive body.

Fig. 1 shows the geometry created by the input file of Table 2. The edge cells of the space are all grounded metallic cells, shown in black, except the left-hand terminal of the resistor, which is shown in red to represent metallic cells at 100 volts potential. The resistive material is shown in yellow. The resistor body is separated from the metal wall at the top and bottom by insulating cells shown in blue. The black line running across the resistor at left is the cut specified by the CURRENT command in Table 2, at cell 10. The program will find the current flowing across this line.

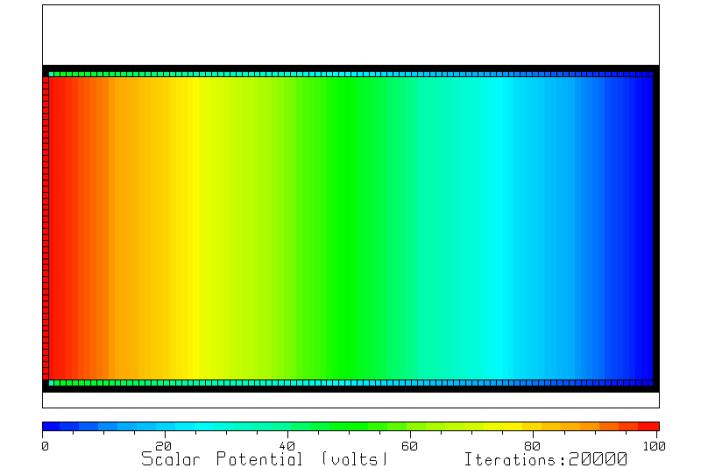

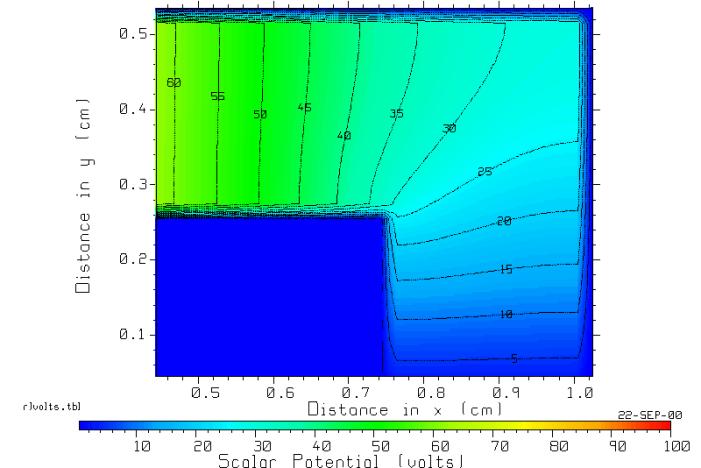

Figure 2 The scalar

potential in the resistor after 20,000 iterations.

Figure 2 shows the scalar potential that the program calculates in the simple resistor. The fixed potential cells at left are outlined in black. The row of insulating cells at the top and bottom of the resistor are also outlined in black to distinguish them from the resistive cells making up the resistor. The scalar potential decreases linearly from 100 volts at left (red) to zero volts at right (blue), progressing through the color scale representing the various voltage levels, yellow for 75 volts, green for 50 volts, cyan for 25 volts and so forth. If you run this problem with RLAPL you will note that the solution does not much change after about 10000 iterations, so the total of 20000 used here is larger than really needed.

The program reports that the current flowing across the line in Fig. 1 is 0.005005388 amps. Since the voltage was set at 100 volts, the resistance is

![]() ohms

ohms

Compared to the true value

of 20,000 ohms, the error is 0.11 percent.

Series Resistors

If we make cells 2 to 50 have resistivity 50 ohm-meters and cells 51 to 101 150 ohm meters. Then we have two resistors in series, each ½ cm long, and we expect the resistance to be 50000 ohms for the first half and 150000 ohms for the second half for a total of 200000 ohms. For 100 volts applied to the resistor, there should be a voltage drop of 25 volts over the 50000 ohm resistor and 75 volts over the 150000 ohm resistor. We can change the input file of Table 2 to define the series resistors with

RESIS_BOX

2 3 51 52 50.

RESIS_BOX

52 3 101 52 150.

The first RESIS_BOX command sets cells 2 to 51 from left to right to 50 ohm-meters and the second RESIS_BOX command sets cells 52 to 101 to 150 ohm-m. Then we run RPLAL to compute the solution.

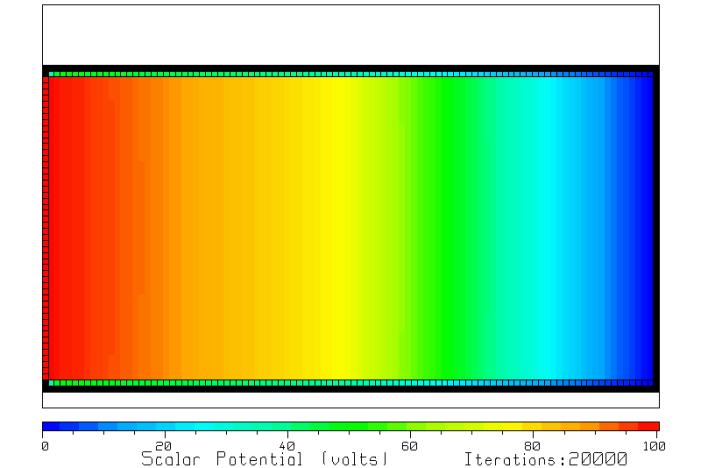

Figure 3 The

scalar potential for series resistors.

Figure 3 shows a

voltage drop from 100volts(red) at left to 75 volts(yellow) in the center of

the resistor, or 25 volts over the low-resistance half. Then the voltage drops from 75 volts in the

center to 0 volts at right over the high-resistance half. The program reports the current flow as

0.000508358 amps, so the resistance is 196,711 ohms, close to the value of

200000 ohms that is expected.

Parallel Resistors

Consider two

resistors side by side each 1 cm long and ¼ cm wide. One has resistivity 50 ohm-m and the other 10 ohm-m. The resistances of 200000 ohms and 40000

ohms are in parallel for a net resistance of 33,333 ohms. To model parallel resistors, make cells 2 to

27 cross-wise have a resistivity of 10 ohm-m,

RESIS_BOX

2 3 101 27 10.

And

cells 28 to 52 have a resistivity of 50 ohm-m,

RESIS_BOX

2 28 101 52 50.

Run RLAPL.

The program reports a current flow of 0.003005329 amps, so the

resistance is 33,274 ohms, close to the expected value.

Bent Resistor

Consider a resistor constructed in an “L” shape. The long leg is 1 cm long, 1/4 cm wide, and has resistivity 10 ohm-m. The short leg is ½ cm long, ¼ cm wide and has the same resistivity. What is the resistance? The centerline path in this resistor is 1.25 cm long, so we can reasonably expect a resistance of about 50000 ohms. But the problem is difficult to solve analytically, and the finite-difference method offers a much more accurate estimate of the resistance.

We can define

this resistor with a cell space of 103 by 54 cells, as follows:

SPACE

103 54

RESIS_BOX 2 28 101 52

10.

RESIS_BOX

77 2 101 27 10.

LINE

1 28 1 52 100.

LINE 2 26 75 26 0.

LINE

75 2 75 25 0.

CURRENT 10 1

10 54

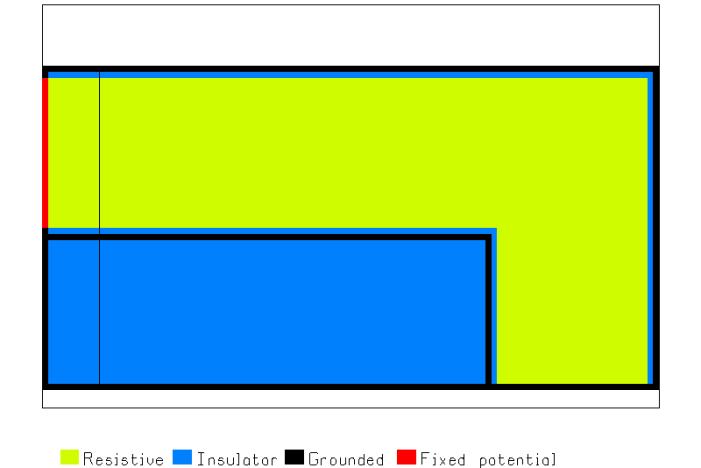

Figure 4 shows the resistor

that results from this definition. The

long leg of the “L” is located across the top and the short leg at right. A LINE command sets the left-hand contact of

the resistor to 100 volts. LINE

commands have been used to set up metal walls along the bottom edge of the

resistor from cell 2,26 to cell 75,26, and along the left edge of the short

leg, from cell 75,2 to cell 75,25.

These metal walls isolate the rectangle at lower left from the rest of

the problem, and the potential in this rectangle will always be zero

volts. Note that the metal walls are

separated from the resistor by an insulator 1 cell wide. The “CURRENT” command asks for the current

crossing the black line shown at left in the figure.

Figure 4 The

L-bend resistor.

Figure 5 The

scalar potential in the L bend resistor.

Figure 5 shows the scalar potential in the L bend resistor after 20000 iterations. As might be expected, the potential varies roughly linearly with distance from the 100 volt contact at upper left to the 0 volt contact at lower right. The distortion in the equipotentials near the bend is of interest. This is more easily seen by graphing the file VOLTS.TBL with CPLOT, as in Figure 6.

Figure 6 The equipotentials near the bend in the bent

resistor.

Fig. 6 shows the

equipotentials in the region of the bend, graphed with CPLOT. The 60 volt equipotentials at left is nearly

perpendicular to the edge of the resistor, as is the 5 volt equipotentials at

the lower right. The equipotentials

near the bend become distorted in shape.

The direction of current flow is perpendicular to the equipotentials,

and the current is largest where the equipotentials are close together. Thus, the current is largest near the inside

corner of the bend.

The RLAPL program

reports that the current flow in the resistor is 0.002181716 amps so the

resistance is 45,835 ohms, which is comparable to the expected value of about

50,000 ohms. The resistance is less

than the mean-path estimate because the current tends to “cut the corner” and

so the path length is effectively shorter than the mean path.

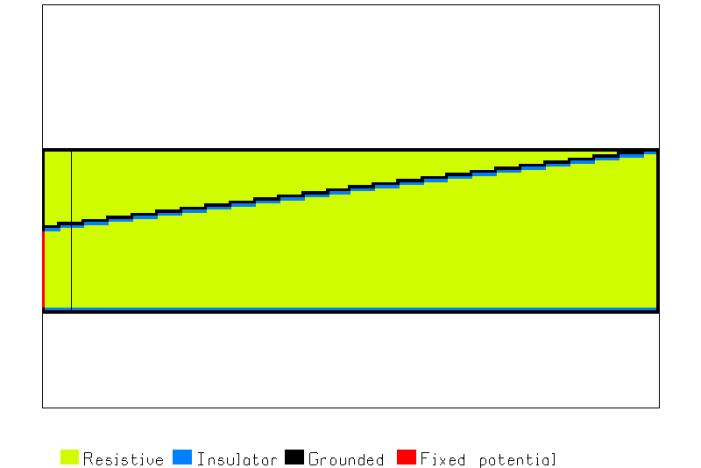

Resistor of Increasing Width

Suppose we have a resistor which is

t=1 mm thick and of resistivity ![]() 10 ohm-m. The

resistor is L=2 cm long, and increases in width from

10 ohm-m. The

resistor is L=2 cm long, and increases in width from ![]() ¼ cm at left to

¼ cm at left to ![]() ½ cm at right. What

is the resistance? The resistance can

be calculated by assuming the resistor is made up of a series connection of

resistors of length dx, and summing up their values to obtain

½ cm at right. What

is the resistance? The resistance can

be calculated by assuming the resistor is made up of a series connection of

resistors of length dx, and summing up their values to obtain

![]() ohms

ohms

This formula is, however, approximate, because it assumes that the current flow in the resistor is parallel to the bottom edge, and that the equipotentials are perpendicular to the bottom edge.

To model this resistor with RLAPL, set the space size to 202 by 54 cells of size 0.0001 mm, Then the resistor is 200 cells long, and should increase in width from 25 to 50 cells. The following commands define the resistor:

CM

Define the resistivity of cells in the body of the resistor

RESIS_BOX

2 3 201 53 10.

CM

Put a line of insulating cells to define the boundary of

CM

the resistor

INSUL

2 28 201 53

CM

Put a line of metal cells to make the field zero in the unused part

CM

of the cell space:

LINE 2 29 201 54

0.

CM

Define the metal contacts on the ends of the resistor

CM

The left edge where the current enters is at 100 volts:

LINE

1 3 1 27 100.

CM

Ask the program to find the current flowing in the resistor:

CURRENT

10 1 10 54

First we use RESIS_BOX to

fill the cell space with resistive material.

Then we define a line of insulating cells from cell 2,28 to cell 201,53

which is the sloped boundary of the resistor.

The resistor is then 200 cells long, and 25 cells wide at the narrow

end, increasing to 50 cells at the wide end.

We put a line of metal cells at zero potential adjacent to the

insulator, from cell 2,29 to cell 201,54.

This keeps the field zero in the upper left corner of the cell space. We set the voltage at the left hand side of

the resistor to 100 volts, and ask for the current crossing a vertical line at

cell 10. Figure 7 shows the geometry of

the resistor.

Figure 7 The resistor of

increasing width.

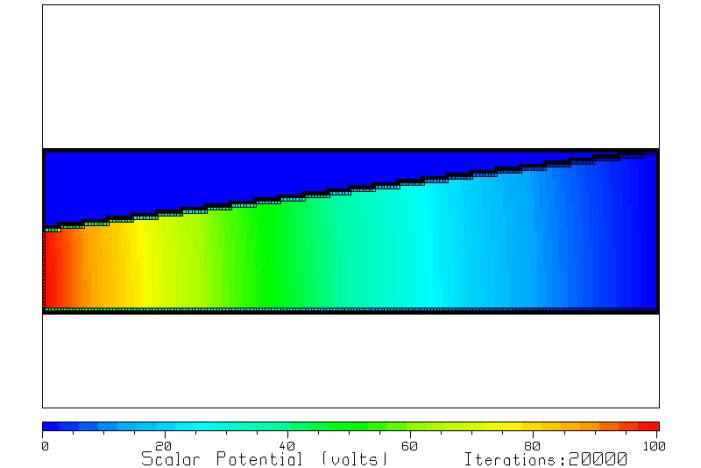

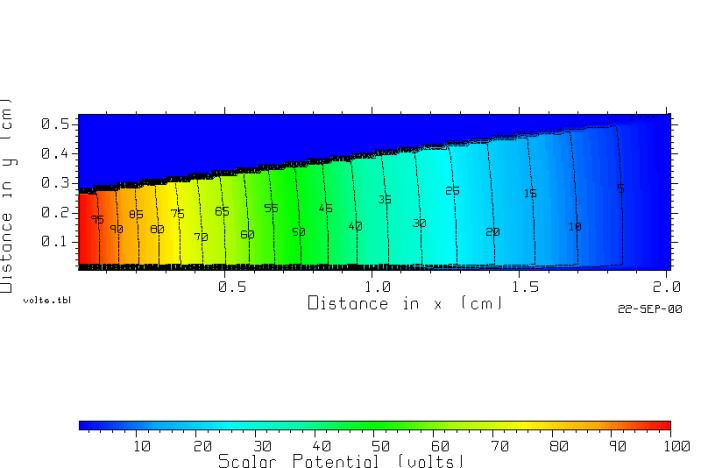

Figure 8 The

scalar potential after 20000 iterations.

Run program RLAPL and let it complete 20,000 iterations. The scalar potential is that shown in Fig. 8. The equipotentials are not perpendicular to the bottom edge of the resistor, but rather are curved as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9 The equipotentials drawn with program CPLOT.

The equipotentials in Fig. 9 are not straight lines perpendicular to the bottom edge of the resistor, as assumed in deriving the formula given for the resistance, above. Hence we expect the value given by the formula will not be exact. The RLAPL program reports the current flow as 0.002002697 amps so the resistance is 49,932 ohms. This is about 10 percent low than the value of 55,452 ohms quoted above.

Notched Resistor

Consider a uniform resistor of length 1 cm, width ½ cm, thickness 1 mm, and resistivity 10 ohm-m. We showed above that the resistance is 20000 ohm. This was modeled with cells of size 0.0001 cm, so that the resistor is 100 cells long and 50 cells wide.

To trim the value of the resistance, a laser beam will be used to make two cuts in the resistive material, of width 0.0001 cm. The cuts are made near the center of the resistor and are of equal length. This forces the current to flow through the gap between the cuts, and increases the resistance. By controlling the width of the gap, the resistance can be controlled. Let us use program RLAPL to find the resistance for a gap width of say 1 mm.

Figure 10 The uniform resistor with notches cut at each side.

Fig. 10 shows the resistor with notches cut at from the edge. The current must flow through the gap between the notches. By controlling the width of the gap, we can control the resistance.

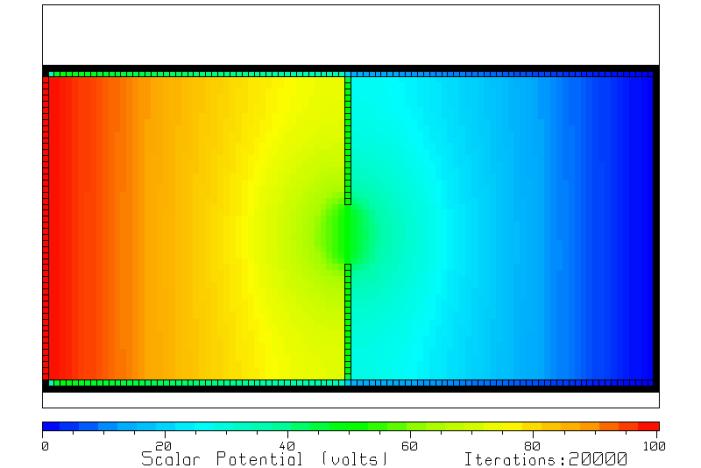

Fig. 11 The scalar potential after 20000 iterations.

Fig. 11 shows the scalar potential after 20000 iterations. Note that the colors at left and at right are not perfectly uniform from top to bottom; the solution may require more than 20000 iterations to converge. Try running it for more iterations. The potential drops from 100 volts (red) at left to about 70 volts (yellow) near the gap, then drops rapidly to 30 volts (cyan) on the other side of the gap, then declines gradually to 0 volts (blue) at right. A graph of the potential with equipotentials lines can be made with CPLOT, see Fig. 12.

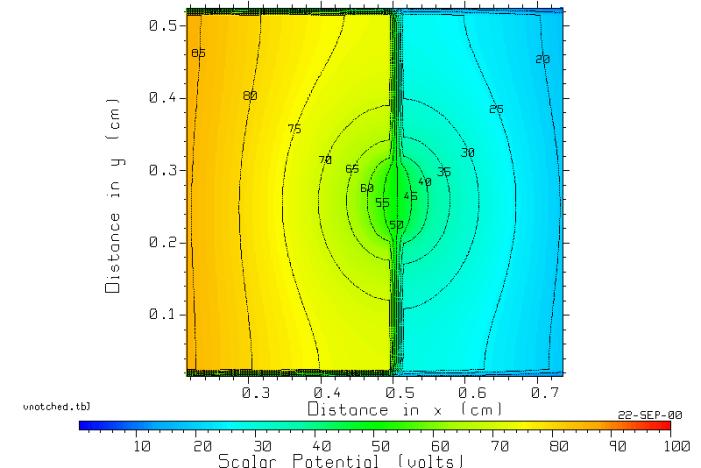

Fig. 12 The equipotentials in the region of the gap.

Fig. 12 shows the

potential in the center of the gap is 50 volts, which we expect from the

symmetry of the problem. The

equipotentials are roughly elliptical in shape surrounding the gap.

The RLAPL program reports the current as 0.003474683 amps, so the resistance with a 1 mm gap is 28,780 ohms, considerably higher than the value of 20000 ohms with no cuts in the resistor.

Conclusion